7. Gradation (weak and strong forms)

When you ask a non-native speaker of english to read out some sentence, they are more than likely to pronounce it differently than if they were to say this sentence as a natural, spontaneous utterance from a native english speaker.

The more explicit pronunciation they might have used when reading the sentence out is of course based on the spelling, and the spelling, in its turn, is based on the way words are pronounced in isolation.

It appears, however, in English, there are quite a number of words that have a particular pronunciation when said in isolation (called the strong form or SF), but, except when they occur in certain positions, have a different pronunciation when they are used in connected speech (called the weak form or WF).

7.1 Gradation (or function) words

In English, there are quite a number of words that have a particular pronunciation when said in isolation (called the strong form or SF), but, except when they occur in certain positions, have a different pronunciation when they are used in connected speech (called the weak form or WF).

Such words are called gradation words, gradation being the technical term for the reduction of strong forms to weak forms.

Consider the English example He has told us, in which three of the four words are gradation words. In this sentence, WFs are used: /hi z toʊld əs/, but in isolation they would have their SFs: /hiː/, /hæz/, and /ʌs/. It will appear in the sections below that GA gradation words typically lose initial /h/ and /w/, and that vowels, when not actually elided, are reduced to /ə/, or to weak /i/ and /u/.

In general, learners tend to use too many SFs, which may make their pronunciation sound unnecessarily formal, or even a little pompous. The use of WFs in English must still be learned and practiced because:

- (i) words whose your mother tongue equivalents have no WFs may have WFs in English, or vice versa, and

- (ii) the form of the English WFs may be different from what might be expected on the basis form your native language equivalents.

In addition to this, you should remember that when reading out a text, and certainly when reading a text in a foreign language, people generally have an inclination to pronounce SFs where WFs should be used.

In order to read texts naturally and competently, you should make a point of using WFs where appropriate. Also, to turn to the perception aspect of this, you may discover that you do not spot WFs in the colloquial pronunciation of native speakers. Some english learner often fail to hear /d/ in He’d like to go, I’d rather not, etc., or /ðət/ in I know that John is right, etc.

Gradation words are always function words. In particular, they belong to the following word classes: the articles, pronouns (voornaamwoorden), auxiliaries (hulpwerkwoorden), prepositions (voorzetsels), conjunctions (voegwoorden). In contrast, major-class words are never gradation words. Major classes are lexical verbs (hoofdwerkwoorden), nouns (zelfstandige naamwoorden), adjectives (bijvoeglijke naamwoorden), and adverbs (bijwoorden).

7.2 Gradation of articles

The gradation words of GA are presented in tables: the second column gives the SF, the third the WF, and the fourth column gives an illustration of the use of the WF.

| Strong Form | Weak Form | Example | |

| a | eɪ | ə | a book |

| an | æn | ən | an ordeal |

| the | ðiː | ðə

Before V: ði |

the milk

the oil |

The SFs of the articles occur when they are accented, as in He is ˈthe /ðiː/ man for

the job. Note, however, that /ðə/ may be the accented form of the as

in I said ˈthe /ðə/ or /ˈðiː/ book, not a /eɪ/ book.

Some

varieties use /ðə/ regardless of the following phoneme: the eagle: [ðə

ʔːgl].

7.3 Gradation of pronouns

The second column gives the SF, the third the WF, and the fourth column gives an illustration of the use of the WF.

| SF | WF | Example | |

| me | miː | mi | Tell me |

| you | juː | ju

also: jə |

You ate it?

You want to come? |

| he | hiː | (h)i | What he says is true |

| him | hɪm | (h)ɪm | You don’t know him |

| his | hɪz | (h)ɪz | Is that his address? |

| she | ʃiː | ʃi | She reads a lot |

| her | hɜr | (h)ər | That’s her husband |

| we | wiː | wi | We know |

| us | ʌs | əs

(let us: /lɛts/ |

It shouldn’t worry us |

| them | ðɛm | (ð)əm | Tell them |

| their | ðɛr | (ð)ər

(before V only) |

Their own fault |

The SFs of these pronouns are used when they are accented. In unaccented positions it is normal to find WFs. Some speakers avoid the form /əm/ or /ðəm / for them, and use the SF. Note:

- /h/ is usually pronounced when a pause precedes, while in other positions it is usually left out: He likes her /hi ˈlaɪks ər/;

- some, that and who are gradation words in certain functions only:

- Some /səm/ cheese, some /səm/ chairs. The SF /səm/ is used when some is accented, but also when it occurs finally, as in I’d like some /aɪd ˈlaɪk sʌm/. When some is equivalent to /sʌm/: some /sʌm/ woman or other, with some /sʌm/ difficulty, some /sʌm/ chairs are a bit wobbly. Also the adverb is always /sʌm/: some /sʌm/ ten years ago.

- that when it is a relative pronoun or when it is a conjunction: I remember the horse that /ðət/ finished second, I remember that /ðət/ he had a limp. Also as in His excuse, that he’d missed the train, was not accepted. When it is a demonstrative pronoun, as in I like that blue one or an adverb, as in It isn’t all that difficult, it is always /ðæt/.

- who is a gradation word when it is a relative pronoun. I know the man who /(h)u/ said this. When it is an interrogative pronoun, it is always /huː/: Who /huː/ said this?

7.4 Gradation of ‘have, will’ and the present pense of ‘be’

The second column gives the SF, the third the WF, and the fourth column gives an illustration of the use of the WF.

The WFs of the auxiliaries have, will, and be (present tense, both as an auxiliary and as a copula (koppelwerkwoord)) are usually contracted with the pronominal form of the subject when this precedes.

The word there, also commonly contracts with these verbs, and has therefore been included in the table. Note that weak /i/ in these forms could also be transcribed /ɪ/, there being no opposition here.

| be | have | hard or would | will | |

| I | aɪm | aɪv | aɪd | aɪl |

| you | jər | juv | jud | jəl |

| he | hiz | hiz | hid | hil |

| she | ʃiz | ʃiz | ʃid | ʃil |

| it | ɪts | ɪts | ɪt̬əd | ɪt̬l |

| there (sg) | ðərz | ðərz | ðərd | ðərl |

| there (pl) | ðərər | ðərv | ðərd | ðərl |

| we | wɪr | wiv | wid | wil |

| they | ðɛr | ðeɪv | ðeɪd | ðɛl |

In informal writing the following spellings occur for these contracted auxiliaries: (I)’m, (you)’re, (he)’s, (I)’ve, (I)’d and (I)’ll. These auxiliary WFs, which consist of a single consonant, typically only occur after a pronominal subject, as in the table above. In other situations, the longer WFs of these auxiliaries are more usual. However, it should be noted that:

- /s,z/ for has, too, may occur after other words (The form /s/ occurs after /p,t,k,f,θ/, /ɪz/ after /s,z,ʃ,ʒ/, and /z/ elsewhere):

The book has /bʊks/ or /ˈbʊkəz/ been reprinted

Mary has /ˈmɛri(ə)z/ done it

Madge has /ˈmæd͡ʒəz/ given it up

- /l/ for will is also used more freely, especially when it is syllabic The others will /ˈʌðərzl/ finish it.

In the table below the longer WFs of these auxiliaries are given.

| SF | longer WF | Example | |

| am | æm | əm | So am I |

| has | hæz | (h)əz | Neither has /niːðərəz/ Eric |

| have | hæv | (h)əv | Tom and Mary have moved |

| had | hæd | (h)əd | Where had they put it? |

| would | wʊd | (w)əd | Matthew would do it |

| will | wɪl | (w)əl | Peter will tell you |

7.5 Gradation of other auxiliaries

The second column gives the SF, the third the WF, and the fourth column gives an illustration of the use of the WF.

In the table below the SFs and the WFs of the remaining auxiliary-forms are given.

| SF | WF | Example | |

| are | ɑr | ər | The boys are there |

| be | biː | bi | I’ll be there |

| was | wʌz | wəz | Mary was here |

| were | wɜr | wər | We were all ill |

| do | duː | də | Do they know this? |

| Before V: du | Do I? | ||

| does | dʌz | dəz | Does Alice like it? |

| can | kæn | kən | They can go now |

| could | kʊd | kəd | He could do it |

| must | mʌst | məs | Must John? |

| Before V: məst | Must Uncle Arnold? | ||

| should | ʃʊd | ʃəd | Mary should know better |

Do not confuse the auxiliaries do and have with the lexical verbs do and have, which are not gradation words:

- He does /dʌz/ the cooking and I do /duː/ the washing up

- She had /hæd/ a hat on

- He had /hæd/ a house built

- I have /hæv/ a holding once a year

Recall that been is always /bɪn/, never /biːn/, as in British English.

7.6 Contractions

The second column gives the SF, the third the WF, and the fourth column gives an illustration of the use of the WF.

With to

The word to contracts with a number of verbs to form single words. These are given in the table below.

| had to | hæt̬ə | We /hæt̬ə/ tell her |

| has to | hæstə | He /hæstə/ be there |

| have to | hæftə | I /ˈhæftə/ do it |

| supposed to | səpoʊstə | She’s /səpoʊstə/ do it |

| used to | juːstə | he /juːstə/ do this |

| want to | wɑːnə | I /wɑːnə/ kiss you |

| going to | gənə | It’s /gənə/ rain |

With not

Not has a WF /nt/, informally spelled n’t, which contracts with auxiliaries, as in He couldn’t /kʊldnt/come. In such cases the auxiliary always has the SF, i.e. we cannot have */kədnt/, for example. In some cases the contractions consist of one syllable. These are given in the table below.

| are not or aren’t | ɑrnt |

| cannot or can’t | kænt |

| do not or don’t | doʊnt |

| will not or won’t | woʊnt |

In questions, not is often written after the subject in formal writing, as in Is it not time Mrs Selkirk took that step? When reading such a sentence out, however, not should be contracted with the auxiliary: /ɪznt ɪt/ etc. The pronunciation /ɪz ɪt nɑːt/ would be very formal.

Note that in order to avoid the clumsy Am I Not? One normally says /ɑrnt aɪ/, and writes Aren’t I? And musn’t is pronounced /mʌsnt/.

7.7 The use of strong forms of auxiliaries

As always, the SF used when the auxiliary is stressed. He ˈwill /ˈwɪl/ have it his way. Note that in tags it is the auxiliary rather than the personal pronoun that carries the stress: I’m supposed to know this, am I? /ˈæm aɪ/ (*/əm ˈaɪ/).

There is, however, a second situation in which auxiliaries must be given their SF. Consider the following sentence: I think we can do it today, but I don’t think we can do it tomorrow. In such a sentence it is normal for the second occurrence of do it to be deleted (left out).

You should observe that when this is done, the auxiliary, which must remain, has its SF: I think we can /kən/ do it today, but I don’t think we can /kæn/ tomorrow. We call the place where the words do it have been deleted a deletion site, and the rule can be phrased as follows:

The auxiliary has its SF immediately before a deletion site.

In the following examples the deletion sites are marked { DS}:

We could /kəd/ all give a little help. At least I could /kʊd/ { DS}, and I suppose Elsie could /kʊd/ { DS}, and Len could /kʊd/ on weekends…

Mary won’t believe this, but perhaps John will /wɪl/ { DS}.

In the following example the deletion site does not immediately follow the auxiliary, which therefore has its WF:

John doesn’t believe it. Do /də/ you { DS}?

When be is a copula, the deletion rule applies to the subject complement (also called the nominal part of the predicate):

Is he the captain? I thought you were /wɜr/ { DS}.

Summarizing: auxiliaries have their SF when they are stressed or when they occur immediately before a deletion site. In sentence-initial position, the SF may also be used.

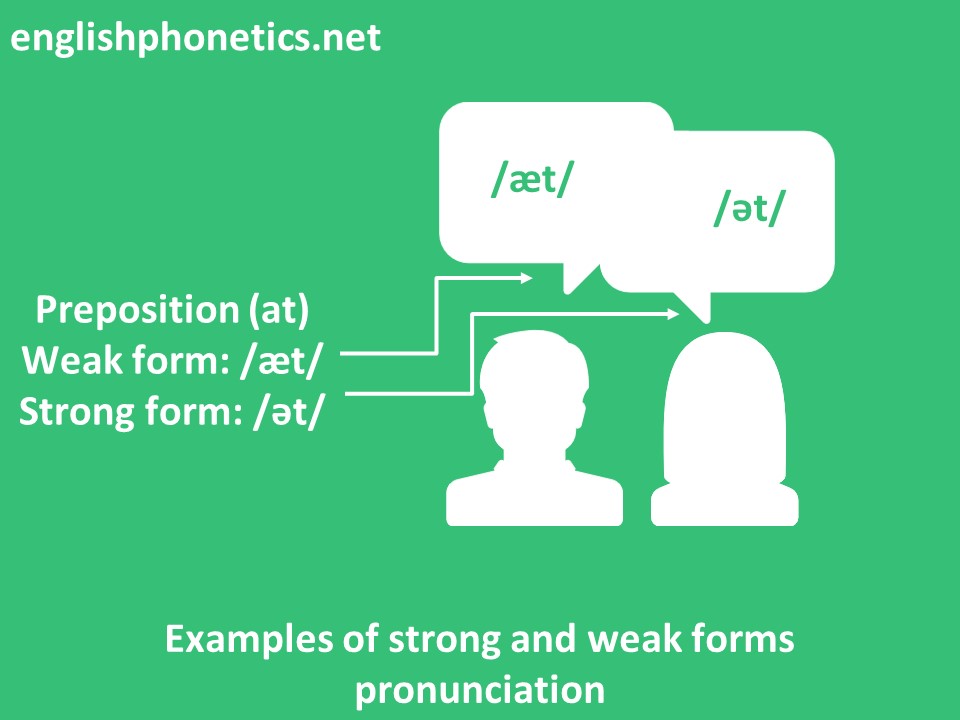

7.8 Gradation of prepositions

The second column gives the SF, the third the WF, and the fourth column gives an illustration of the use of the WF.

The following prepositions have WFs and SFs:

| SF | WF | Example | |

| at | æt | ət | at home |

| for | fɔr | fər | for William |

| from | frʌm | frəm | from Angela |

| of | ʌv | əv | a view of LA |

| ə in: | a cup of tea, a pint of milk, etc. | ||

| till | tɪl | t(ə)l | till Christmas |

| (in)to | tuː | tə | to go into business |

| until | ʌnˈtɪl | ənˈtɪl | until we die |

Before vowels, many speakers use /tu/ for the weak form of to, as in to Ann, to eat.

Again, the Sf is used when the word is stressed: I don’t like the people who talk ˈat /æt/ one rather than with one.

Just like auxiliaries, prepositions may occur before a deletion site, in which case they, too, have their SF. Consider the sentence: They are looking at the problem now. If we could move the words the problem away from at, then this preposition would occur before a deletion site. We can do this by making the sentence passive: The problem is being looked at /æt/ { DS} now.

Or by turning it into a relative clause:

This is the problem that they are looking at /æt/ { DS} now.

Or by querying ’the problem’, that is, by asking:

What are they looking at /æt/ { DS} now?.

Here are some further examples:

I don’t know who he has got it from /frʌm/ { DS}.

What are you doing that for /fɔr/ { DS} ?.

In those days kissing in public was not approved of /ʌv/ { DS}.

Note that also the infinitive particle to may occur before a deletion site, as in: Marry you? You know I’d love to /tuː/ { DS} but my husband won’t let me.

Summarizing: prepositions and the infinitive particle to have their SF when they are stressed or when they occur immediately before a deletion site. When an unstressed preposition occurs before an unstressed personal pronoun, the preposition usually also has its SF.

7.9 Miscellaneous gradation words

The second column gives the SF, the third the WF, and the fourth column gives an illustration of the use of the WF.

The following gradation words have not been discussed so far:

| SF | WF | Example | |

| as | æz | əz | as white as snow |

| than | ðæn | ðən | better than ever |

| and | ænd | ən | black and blue |

| but | bʌt | bət | poor but happy |

| or | ɔr | ər | three or four |

| because | bɪkɑːz | bɪkəz | not because I like it |

The SFs occur when the words are stressed. The SF of than will not normally occur. As, on the other hand, frequently has its SF at the beginning of a clause. It is always /æz/ when it is equivalent to As /æz/ the gale increased in force, more and more reports of uprooted trees and blown-off rooftops were coming in.