9. Aspiration, glottalization, and flapping

This section looks at some processes that can apply to the English fortis stops. The resulting sounds are allophones of the phonemes /p, t, k/.

9.1 Stops and voice

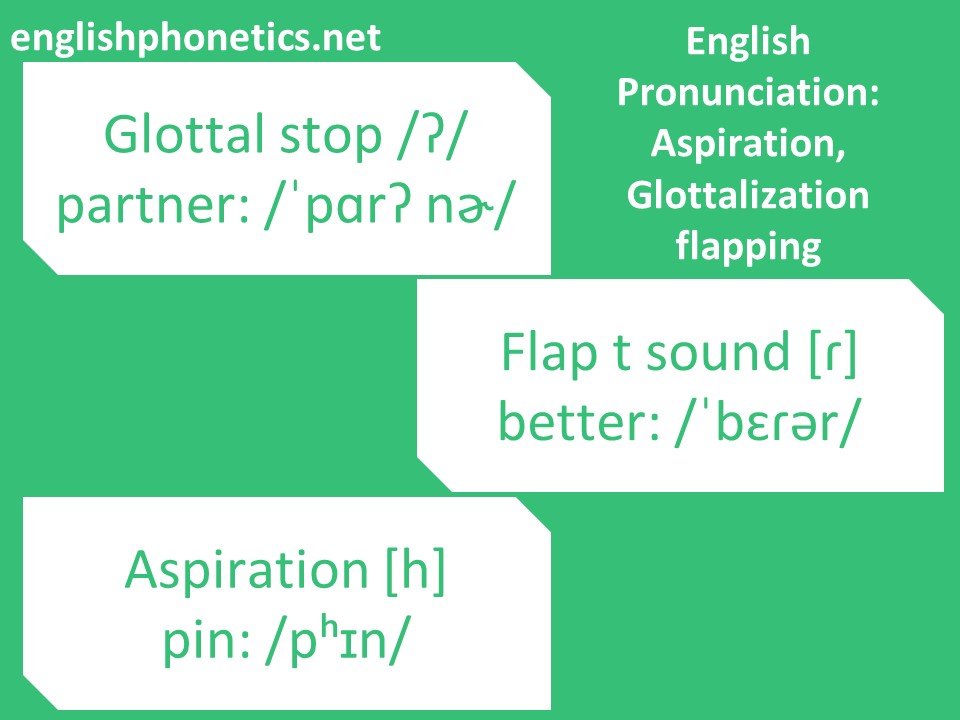

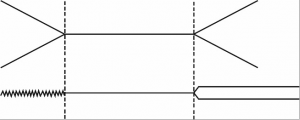

Below is a schematic representation of the movements of the articulators in the production of a stop. The two articulators for [p,b], for instance, are the upper lip and the lower lip; for [t,d] they are the tip plus rims of the tongue and the alveolar ridge; and for [k,g], they are the back of the tongue and the soft palate.

The figure represents the three stages in the articulation of a stop:

During the closing stage (1), the articulators are brought together to form a complete closure at some point in the speech tract, behind which the air from the lungs is trapped.

This is followed by the compression stage (2), during which the air pressure behind the closure will increase as more air continues to be expelled from the lungs.

The third stage is the release of the closure (3): if the articulators are separated abruptly, the air will rush out from behind the closure, which gives rise to the characteristic popping sound of a stop.

Stops that are pronounced with a sudden release are also called plosives, because the sudden release causes the air to literally explode outward. Try and become aware of the gesture represented in Figure 2 by silently mouthing [apa], [ada] etc.

A stop is fully voiced when the vocal cords vibrate throughout its articulation, from the beginning of stage 1 to the end of stage 3, as for /b/ in GA and AN label.

label – /ˈleɪbəl/

When there is no vocal cord vibration at any time during the articulation of a stop, it is completely voiceless, like /t/ in GA and AN stem.

stem – /stɛm/

When vocal cord vibration occurs during part of the articulation of a stop only, the stop is partly devoiced, as in GA bead.

bead – /biːd/

If the stop is voiceless, and the open glottis is maintained for a while during the production of a following vowel or sonorant (that is, stage 3 is also voiceless), the stop is aspirated. We will see that some of the major differences between GA and AN stops are due to a different timing of the beginning or the end of vocal cord vibration relative to the movements of the articulators.

9.2 Aspiration

When we compare the stops in GA ski and key we can hear a short puff of air immediately after the release of /k/ in key, which is usually absent from that in ski. The same contrast can be observed in pairs like pie versus spy and till versus still.

ski – /skiː/

key – /kiː/

pie – /paɪ/

spy – /spaɪ/

till – /tɪl/

still – /stɪl/

The difference between the stops in these pairs lies in the beginning of vocal cord vibration (known as the ‘voice onset’). In ski, the voice onset coincides with the release of the stop, but in key, there is a delay. This causes the first portion of the vowel /iː/ to be devoiced, which as a result causes us to hear an h-like sound after the stop. This process, which is called aspiration, is symbolized by means of a superscript h, as in [kʰi:] or, phonetically more accurately, by means of a devoiced vowel, as in [ki̥i:], which is meant to indicate that the first portion of the vowel is whispered and the second voiced.

Although aspirated stops – with a considerably shorter voice delay – occur in many accents spoken where the /p,t,k/ are unaspirated.

The effect of aspiration can be demonstrated by placing a lighted match about an inch away from the lips of a native speaker – careful now! – and asking them to say a word like pin. With luck, the flame should be blown out by the puff of breath that accompanies the aspirated [pʰ] in pin but much less so, if at all, when the word spin is pronounced.

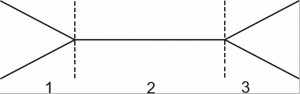

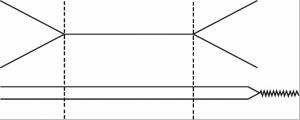

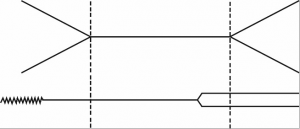

The figures below illustrate the difference in the voice onset for aspirated and unaspirated stops. The parallel lines represent an open glottis, the wavy line a vibrating glottis.

9.2.1 Approximant Devoicing

Like vowels, the GA approximants /l,r,j,w/ can follow syllable-initial /p,t,k/, so that the

voice delay that occurs after the release of fortis stops may also affect a following

approximant.

Examples would be pure and twin.

pure – /pjʊr/

twin – /twɪn/

The effect is particularly striking in the case of /tr/, which is usually pronounced as a completely voiceless affricate. In words like pure and twin, /j/ and /w/ tend to be partly devoiced: [pj̥ʊr, tw̥ɪn]. Note that the devoicing of /j/ in GA pure is paralleled by that of AN /j/ in the diminutive ending and the personal pronoun je, as in hapje, heb je, koekje.

hapje – /ˈhɑpjə/

The devoicing of approximants automatically leads to the generation of (voiceless) friction, as can easily be heard and felt when you slow down AN hapje to [ɦɑpçːːjə]. Exactly the same goes for devoiced GA /l,rj,w/.

9.2.2 Distribution of aspirated stops

Aspiration affects syllable-initial GA /p,t,k/. When GA /s/ is the first consonant of the syllable, there is no aspiration. This accounts for the presence of aspiration and approximant devoicing in the words in the first table below. Aspiration is present in the first three lines of words; there is both aspiration and approximant devoicing in the second three.

Aspiration

peel – /piːl/

recall – /riˈkɑːl/

today – /tuˈdeɪ/

Other examples

"return ten possess call caress appeal"

Aspiration and Approximant Devoicing

pure – /pjʊr/

twin – /twɪn/

betray – /biˈtreɪ/

acute – /əˈkjuːt/

Other examples

"queen repute predict tremendous cravat"

The words below have no aspiration and/or approximant devoicing. Note in particular the lack of aspiration in words like spaghetti, stability, skill, etc., and the lack of approximant devoicing in display, distract, obscure, where /s/ precedes the stop in the onset.

Lack of aspiration

spaghetti – /spəˈgɛt̬i/

stability – /stəˈbɪlət̬i/

skill – /skɪl/

Other examples

"spin stern aspire restore discuss musketeer"

Lack of both aspiration and approximant devoicing

display – /dɪˈspleɪ/

distract – /dɪˈstrækt/

obscure – /əbˈskjʊr/

Other examples

"spray string screen splenetic strategic sclerosis"

Ambisyllabic GA /p,t,k/ are not aspirated. While aspiration is always present in coupon, latex, acorn, it is absent in open, later, acre (except in a very formal style of pronunciation).

The /p/ in open, for instance, is subject to WSP and as a result is ambisyllabic, and therefore fails to be aspirated. By contrast, the /t/ in latex, which is followed by a strong vowel, is not affected by WSP, and is aspirated.

Further examples are found below. Thus, [k] in reckon is similar to AN [k] in rekken, and [p] in happy is similar to AN /p/ in Appie.

Aspiration occurs in

biped – /ˈbaɪpɛd/

latex – /ˈleɪtɛks/

viscount – /ˈvaɪkaʊnt/

Ampere

suntax

encore

9.3 Glottal reinforcement (glottalization) and glottal stopping (glottaling)

In syllable-final position, GA /p,t,k/ as in sip, sit, sick or sips, sits, six, tend to be glottalized (or glottally reinforced). A glottalized stop is produced when the oral closure for the stop is accompanied by a simultaneous closure of the vocal cords.

The closure of the glottis may also take place just before the oral closure, in which case we speak of a pre-glottalized stop:

In either case, the auditory impression that is created is that of a sudden silence: this is due to the sudden closure of the glottis, which causes the vocal cord vibration for the preceding voiced sound to be cut off abruptly. GA tends to have glottalized as opposed to pre-glottalized /p,t,k/, the latter being common in British English. Glottalization is more common for /t/ than for /p/ and /k/.Before a pause, glottalized /t/ is normally unreleased or, strictly speaking, released inaudibly. Owing to the presence of the glottal closure, the air from the lungs is compressed behind the vocal cords rather than behind the alveolar contact higher up in the speech tract.

As a result, there will not be enough air trapped behind the oral closure for an explosion to occur, and the release will be inaudible.

Before a pause, /p/ too is usually unreleased: while the lips continue to be closed the soft palate is lowered, allowing the air to escape inaudibly through the nose. Alternatively, /p/ may have a weak but audible oral release. This is in fact the most common realization for final /k/, as in sick.

In coda-final positions, GA /t/ may also be realized as a glottal stop. In this case, we speak of glottaling (or glottal stopping) rather than glottalization. The difference between the two lies in the absence of an alveolar contact for glottaled /t/: the oral closure is replaced with a glottal closure, not accompanied by it:

sit [sɪʔ]

sit – [sɪʔ]

button [ˈbʌʔn]

button – [ˈbʌʔn̩]

atlas [ˈæʔləs]

atlas – [ˈæʔləs]

9.3.1 Distribution of glottally reinforced and glottaled stops

Glottalization

Glottalization affects unisyllabic GA /p,t,k/ in the coda, if preceded by a voiced sound. Below are some examples.

Glottalization before p

cap – /kæp/

Also

cops

harpsichord

helped

campsite

Glottalization before t

cat – /kæt/

Also

cart

atlas

can’t

halts

Glottalization before k

lick – /lɪk/

Also

sacked

bark

tanks

huckster

No Glottalization

Glottalization is absent when there is no voiced sound preceding /p,t,k/, and when /p,t,k/ are ambisyllabic.

No Glottalization before p

lisp – /lɪsp/

No Glottalization before t

best – /bɛst/

Also

opt

No Glottalization before k

mask – /mæsk/

Ambisyllabic p

April – /ˈeɪprəl/

Also

apple

ample

corporal

Ambisyllabic t

mattress – /ˈmætrəs/

Also

metal

central

Santa

Ambisyllabic k

orchid – /ˈɔrkɪd/

Also

buckle

Berkeley

uncle

Glottaling

Glottaling of GA /t/ may be viewed as a variable extension of glottalization. The rules have

comparable environments, except that glottaling only affects GA /t/, and

/t/ must be final in its coda.

It may therefore apply in

cat, cart, felt, resentment, or atlas.

atlas – /ˈætləs/

It does not, however, apply in cap, cats, eighth, or central.

central – /ˈsɛntrəl/

Special mention must be made of /t/ before syllabic /n/, as in cotton, buttoned, which, though ambisyllabic, is always replaced with [ʔ]:

cotton – [kɑːʔn̩]

buttoned – [bʌʔn̩d]

9.3.2 Nasalization and nasal deletion

It is helpful at this point to introduce two further rules. Nasalization causes the soft palate to be lowered during a vowel before a nasal: the lowering of the soft palate which is required for nasals anticipates the nasal’s oral closure. The rule, which is variable, affects any vowel before a nasal in the same syllable (whether or not ambisyllabic). So it will apply in keen and keener, but not in the first syllable of keynote. Vowels are also partially nasalized after nasals, as in mad, mile, note, knife.

Nasal deletion deletes the oral closure (bilabial for /m/, alveolar for /n/, velar for /ŋ/), so that just a nasal vowel is produced. It applies before a voiceless stop in the same syllable (whether or not ambisyllabic). So it applies in camp, can’t, thank and in camper, central, thanking, but not in campaign, centrality or concord (/ˈkɑːŋkɔrd/ (noun)).

The combined effect of the two rules is therefore:

Vnt becomes v᷈t

Vmp becomes v᷈p

Vŋk becomes v᷈k

Now review the conditions in which aspiration, glottalization, nasalization, and nasal deletion occur. Which of these rules apply to /mp/ in:

(a) camp;

(b) camper;

(c) campaign?

As you will have determined for yourself, aspiration applies to /p/ in campaign, since it is unisyllabic and syllable-initial in /(kæm)(ˈpeɪn)/. Glottalization applies to /p/ in camp, because it is unisyllabic and occurs in the coda after a voiced sound. Nasalization applies to all three /æ/’s, since in all three cases it is followed by a nasal in the same syllable. And nasal deletion applies to /m/ in both camp and camper, because in either case /p/ occurs in the same syllable as /m/: /(kæmp)/, /(kæm(p)ər)/. So we pronounce:

(a) [kʰæ̃p͜ʔ]

camp – /kæmp/ [kʰæ̃p͜ʔ]

(b) [ˈkʰæ̃pər]

camper – /ˈkæmpər/ [ˈkʰæ̃pər]

(c) [kʰæ̃mˈpʰeɪn]

campaign – /kæmˈpeɪn/ [kʰæ̃mˈpʰeɪn]

Finally, we need to look at the pronunciation of GA /ntn/. The operation of nasalization, nasal deletion, and t-glottaling in words like mountain and sentence will have quite spectacular effects. To take sentence as an example: It will be syllabified as /(sɛn(t)əns)/. Of course, /n/ will be syllabic, so /(sɛn(t)n̩s)/. Nasalization gives [sɛ̃ntn̩s]., and nasal deletion [sɛ̃tn̩s]. Finally, glottaling leads to [ˈsɛ̃ʔn̩s].

sentence – /ˈsɛntəns/ [ˈsɛ̃ʔn̩s]

The same goes for mountain.

mountain – /ˈmaʊntən/ [ˈmaʊ̃ʔn̩]

Advice for learners:

Because of its frequency, it would be a good idea to work on glottaled /t/ first. One way to learn to produce this sound in words like sit is to pronounce /sɪ/ with a very short vowel which is chopped off abruptly as you suddenly hold your breath. The effect is [sɪʔ]. To produce a pre-glottalized stop in a word like sits, you can use the same method: say /sɪ/ but now hold your breath a little longer and then pronounce /ts/: [sɪʔ- ts]. Glottalized stops, which are more common in GA than pre-glottalized ones, may be a little more difficult to pronounce. For a glottalized stop you need to reduce the duration of the glottal closure so that its onset coincides with that of the oral closure.

Remember that in absolute coda-final position glottaled /t/, i.e. [ʔ] is probably more common than glottalized /t/; so try to pronounce a glottal stop in sit, football, it was, let them, atlas, partly and the like. Pay special attention to glottaled /t/ before a syllabic nasal, as in button, certain, mountain: [ˈbʌʔn̩, ˈsɜrʔn̩, ˈmaʊ̃ʔn̩].

button – /ˈbʌtən/ [ˈbʌʔn̩]

certain – /ˈsɛrtən/ [ˈsɜrʔn̩]

mountain – /ˈmaʊntən/ [ˈmaʊ̃ʔn̩]

Schwa tends to be nasalized and raised considerably in the sequence /-ənt/, which may sound rather like [ɪ̃ʔ]. As a result, the second and third syllable of a word like commitment sound rather like those in mitt and mint, respectively: [kəmɪʔmɪ̃ʔ].

commitment – /kəˈmɪtmənt/ [kəˈmɪʔmɪ̃ʔ]

Avoid overgeneralizing glottalization or glottaling to lenis stops: partly is [ˈpɑrtʔli] or [ˈpɑrʔli], but hardly is [ˈhɑrdli]. The vowel is considerably longer in the latter word but, more importantly, there is no glottal closure for /d/: the vocal cord vibration for the vowel /ɑː/ is continued right through to the end of the word.

partly – /ˈpɑrtli/ [ˈpɑrʔli]

hardly – /ˈhɑrdli/ [ˈhɑrdli]

9.4 Ambisyllabic t, d: flapping, voicing, elision

Three Related Processes

In ordinary conversational styles, ambisyllabic /t,d/ are realized either as [d] or [ɾ]. The first arises through t-voicing, and the second through /t,d/-flapping. A third possibility arises because of /t,d/-elision. As a result of these processes, the opposition between ambisyllabic /t – d/ tends to be lost, so that pairs like atom– Adam, parity – parody but also winter and winner tend to be homophonous.

atom – /ˈæt̬əm/ [ˈæɾəm]

Adam – /ˈædəm/ [ˈæɾəm]

parity – /ˈpɛrət̬i/ [ˈpɛrəɾi]

parody – /ˈpɛrədi/ [ˈpɛrəɾi]

winter – /ˈwɪntər/ [ˈwɪ̃nə̃r]

winner – /ˈwɪnər/ [ˈwɪ̃nə̃r]

t-Voicing

t-Voicing will affect ambisyllabic /t/ after /n/ in certain words only. These words will vary from speaker to speaker, but common examples are seventy, certainty, carpenter. So pronounce these words /ˈsɛvn̩di/ etc.

seventy – /ˈsɛvənti/ [ˈsɛvə̃ndi]

Ambisyllabic /t/ may also be voiced to /d/ word-finally, as in the moment is, the treatment of. These /-nd/ clusters do not undergo flapping, and are treated like any such cluster in words that have –nd in the spelling, like sender (Rhodes 1992).

t/d-Elision

t/d-Elision occurs after /n/ in a strong syllable, as in center, fantasy, mental, and in phrases like went on, can’t afford, in front of.

center – /ˈsɛntər/ [ˈsɛ̃nə̃r]

fantasy – /ˈfæntəsi/ [ˈfæ̃nə̃si]

in front of – /ɪn ˈfrʌnt əv/ [ɪn frʌ̃n əv]

Elision of /d/ is less common; it may occur in words like fundamental, indication, under, kinda (i.e. kind of) and in phrases like send it, stand up.

fundamental – /ˌfʌndəˈmɛntəl/ [ˌfʌ̃nəˈmɛ̃nəl]

kinda – /ˈkaɪndə/ [ˈkaɪ̃nə̃]

Verging on substandard are pronunciations like /ˈɪnərˈduːs, ˈhʌnərd, for introduce, hundred, where the switching around of /r/ and /ə/ creates the environment for the elision of /d/.

Flapping

In words like atom – Adam, metal – medal, writer – rider both /t/ and /d/ are normally voiced and pronounced as a single tap of the tip of the tongue against the alveolar ridge. The articulation of flapped /t,d/, for which the symbol [ɾ] is used, is not unlike that of Spanish /r/ in pero, or Amsterdam /r/ in a word like serie. However, flapped /t,d/ do not have the friction that may be heard in the sound.

Flapping typically affects ambisyllabic /t,d/ after vowels. There may also be an /r/ before /t,d/. Recall that ambisyllabic consonants are created by WSP (I) or by liaison (II). Here are some examples. Pronounce them.

| I | II | ||

| t | d | t | d |

| hitting | kidding | hit Annette | read all of it |

| liter | shoddy | hit Anne | hid a treasure |

| bottle | heading | write a letter | made in Taiwan |

| Bottom | rider | quite at ease (2x) | ride a horse |

| Ghetto | avocado | meet a friend | he invited Ollie |

| Waiting | wading | bright eyes | a bad egg |

| hearty | hardy | start off | shored up |

Here are some questions you should be able to answer. Why don’t we get flapping in a tease, but do we get it in at ease?

a tease – /ə tiːz/ [ə tʰiːz]

at ease – /æt iːz/ [æɾ iːz]

And why don’t we get it in latex, but do we get it in later?

latex – /ˈleɪtɛks/ [ˈleɪtʰɛks]

later – /ˈleɪtər/ [ˈleɪɾər]

And why in my late ex?

my late ex – /leɪt ɛks/ [leɪɾ ɛks]

Also recall that in words like button, cotton, mountain, where /t/ appears before syllabic /n/, we always get t-glottaling, even though /t/ is ambisyllabic.

As a result of flapping, the members of pairs like futile – feudal, writer–rider, liter – leader, metal – meddle, waiting – wading, latter – ladder are homophones.

futile – /ˈfjuːt̬əl/ [ˈfjuːɾəl]

feudal – /ˈfjuːdəl/ [ˈfjuːɾəl]/

writer – /ˈraɪt̬ər/ [ˈraɪɾər]

rider – /ˈraɪdər/ [ˈraɪɾər]

liter – /ˈliːt̬ər/ [ˈliːɾər]

leader – /ˈliːdər/ [ˈliːɾər]

metal – /ˈmɛt̬əl/ [ˈmɛɾəl]

meddle – /ˈmɛt̬əl/ [ˈmɛɾəl]

waiting – /ˈweɪt̬ɪŋ/ [ˈweɪɾɪ̃ŋ]

wading – /ˈweɪdɪŋ/ [ˈweɪɾɪ̃ŋ]

latter – /ˈlæt̬ər/ [ˈlæɾər]

ladder – /ˈlædər/ [ˈlæɾər]

In at least one context, however, Canadian English maintains a distinction. This is when /aɪ, aʊ/ precede /t,d/, as in writer–rider, right on! – ride on!, a lout in the house – allowed in the house. Before voiceless obstruents, Canadian English has centralized [ʌɪ, ʌʊ] (which causes about the house to sound somewhat like ‘abote the hoce’ or ‘aboot the hoos’). These allophones are also used before /t/ in a flapping context, so that writer – rider, for instance, are different, not because of the consonants, but because of the vowels: [ˈrʌɪɾər] – [ˈraɪɾər].

9.4.1 Flapping and other rules

In words like winter, center, Atlantic, in which ambisyllabic /t/ follows /n/, a number of rules can apply:

- Flapping can apply after (nasalization and) nasal deletion. GA /wɪntər/ becomes [wɪ᷈tər], and, because ambisyllabic /t/ is now between vowels, then becomes [wɪ᷈ɾər].

- t/d-deletion may apply to produce [wɪ᷈nər]. In practice, because the nasalization is likely to be maintained during the flap, the members of pairs like winter – winner will tend to be homophonous in unguarded speech.

Notice also in this connection that the following two utterances are distinct because of the /æ/ – /ə/ opposition in can’t – can:

you can’t eat it – [jəkæ᷈ɾiːɾɪt]

you can eat it – [jəkən iːɾɪ]

However, the following two sentences would be (near-)homophonous.

But you can’t eat it! – [bətʃəˈkæ᷈ɾiːɾɪt]

But you can eat it! – [bətʃəˈkæ᷈n iːɾɪt]

9.4.2 Clitic “to”

Special mention needs to be made of to, as a preposition (to the door), an infinitival conjunction (to go), or as part of words like tomorrow, together. It behaves as though it was part of the preceding word. Such verbal parasites are known as clitics.

It is easy to see that the behavior of to will have certain consequences. As a result, flapping applies to the /t/ in go tomorrow, all day today, fly to Boston.

go tomorrow

fly to Boston

Also t-voicing is frequent in cases like They seem to think…, It‘d be wrong to say…, They’re open today.

they seem to think

hard to believe

Because geminate consonants do not occur inside words, hard to believe, which through t-voicing is /hɑrd dəbəliːv/, becomes /hɑrd əbəliːv/. Because of flapping, it will come to sound just like heart a believe. Can you explain why flapping applies to heart a?

9.4.3 Flapping and native speakers: three questions

- Why is it that many native speakers are reluctant to admit that flapping occurs in their own pronunciation, and may express the view that pronunciations like [ˈtwɛ᷈ni, ˈmæ᷈ɾər, ˈɪnərˈnæʃnəl] are ‘sloppy speech’ and are really incorrect?

- On one occasion, a local English professor in Atlanta, Georgia, referred to the ill-fated ocean-liner “Titanic” as the /taɪˈtæntɪk/. Although the puzzled looks on the faces of her non-native audience caused her to pause, it was only to repeat the word in the same way, much as if she was beginning to have her doubts about her listener’s familiarity with this well-known shipping disaster rather than about her own pronunciation of the ship’s name. Can you explain why she pronounced the word the way she did?

- Young children learning to write have been found to produce forms like bodom, woodr, bedr, nodesen, prede, for bottom, water, better, noticing, pretty; and mitle, nobute for middle, nobody. What does this suggest?

9.4.4 Summary

Here is a brief survey of the various realizations of ambisyllabic /t,d/.

- Flapping of ambisyllabic /t,d/:

- Realization: [ɾ], i.e. a rapidly pronounced [d]

- Condition: after vowels (or vowel plus /r/).

- Examples:

Via WSP

liter leader see you tomorrow

metal medal go to Paris

hurtle hurdle too far to walk

Via Liaison

right on ride on

heart attack hard attack

hit it hid it

- Voicing of ambisyllabic /t/

- Realization: [d]

- Condition: after /n/ in reduced syllables; or after /l/; or /t/ in to after any voiced consonant

- Examples

Via WSP

talented they seem to think

certainty it’s wrong to say

altogether all together

penalty live together

Via liaison

the moment is

the treatment of

built up

- Elision of ambisyllabic /t/

- Realization: [n], or [ɾ]

- Condition: after /n/ in strong syllable

- Examples

Via WSP

winter

fantasy

mental

Via Liaison

she went on

I can’t afford it

In front of